We all know there are problems with the next American president. For us, Jew’s harpers, or *trump* players, there is one extra problem. During his first presidency *trump* players already complained that Donald Trump’s election made it difficult to search for *Jew’s harp*-related stuff online. You used to get some search results about your favorite instrument using that particular name *‘trump’* for it, but this got completely obscured by new links relating to the president. For once, let me make a precise musicological hypothesis: on the internet the name *‘trump’* will be used about half as much for the instrument compared to pre-president Trump years. (Full disclosure: I am not going to test this.)

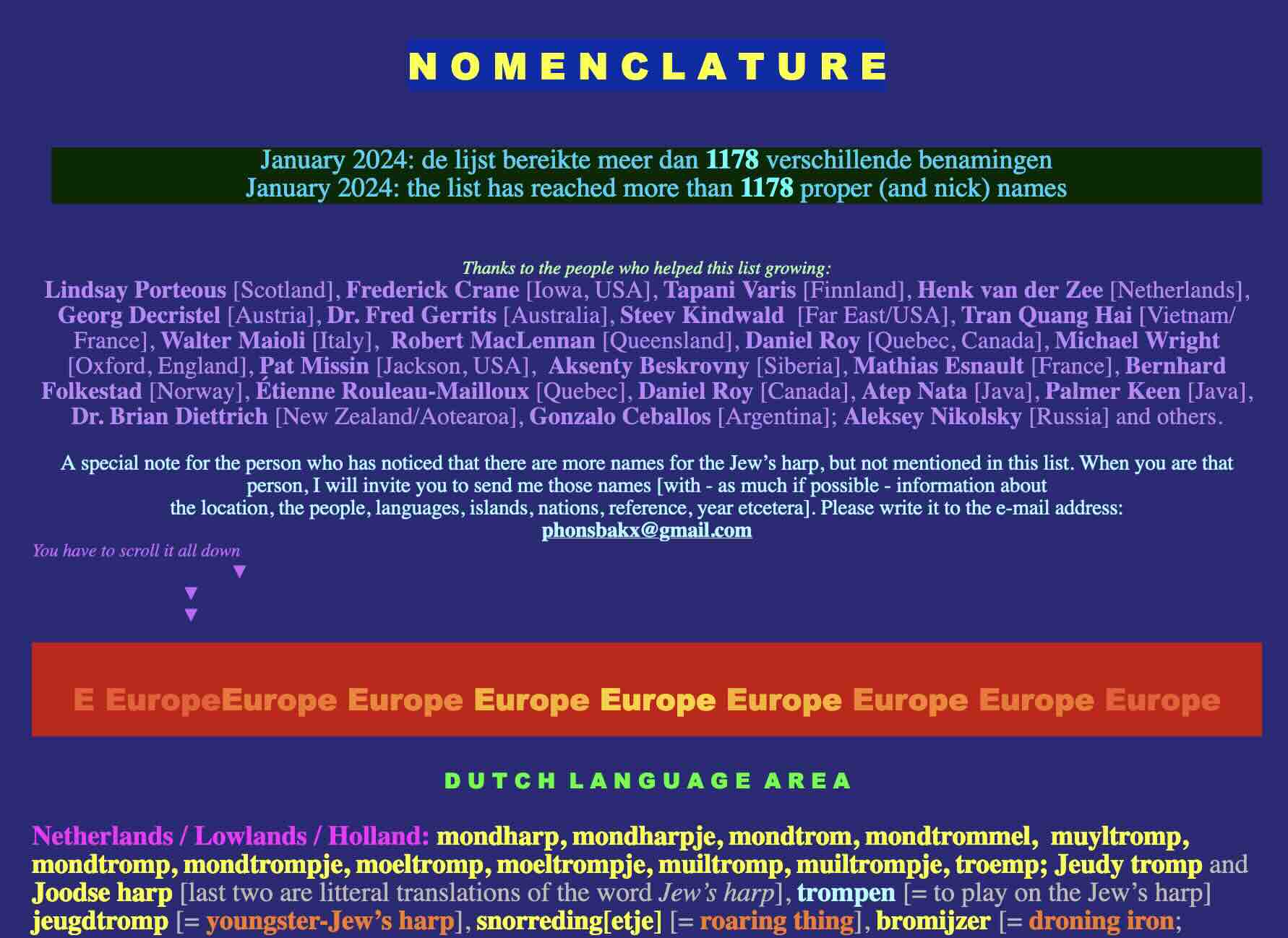

Now, how to search online if your preferred term for the most accessible, most adorable, most transportable instrument happens to be *‘trump’*? By informing yourself about all the other names in existence. ‘Trump’ is but one of more than 1100 names for the same instrument. Phons Bakx, the renowned Dutch Jew’s harp player and researcher, recently shared the latest version of his list with me. Carefully collected during decades of research, with the same rigour that anthropologist Bakx applied earlier to investigations into other obscure instruments, like the bullroarer and a certain non-Tibetan type of singing bowl played on the countryside of Brittany (France).

So check out the 1100+ names for *Jew’s harps*, go to this page

http://www.antropodium.nl/Duizend%20Namen%20Mhp%20voorw%20ENG.htm

and click on this line

(Click here) ► for the Nomenclature of Jew’s harp Names

Be patient if the list does not show up immediately! If there is a warning, ignore it and click ‘continue’. You might also try this one directly:

https://www.antropodium.nl/Duizend%20Namen%20Mhp%20NOMENCLATUUR.htm

Of course, many names for these ‘marranzano pancakes’ (a term actually in use in the States) are quite common and well-known. In Siberia and far beyond, many people know the *khomus*, here in Taiwan more and more people are becoming familiar with the *lubuw* and in Germanic-speaking countries we have the *Maultrommel*, *mondharp* and *mouth harp*. In South Africa, the Xhosa people’s *isitolotolo* is little-known but gee whiz, what a beautiful name it is!

With ever better translating tools (AI!), we may expect more and more reports around the world about President Khomus, President Isitolotolo, President Lubuw and so on in the next four years – you can read the 1150 other variations for yourself but I continue to use some names here, like *this*, so you know what I am talking about.

Meanwhile excitement is building up here in Taiwan, this time for non-political reasons. Final preparations are made now for the truly grand World Jaw Harp Music Festival. One that was envisioned many years ago, but which due to corona become a rather small-scale event in 2022 (see my photos here). But now it has grown to impressive proportions, with musicians attending from all over the place, plus of course a huge representation of local and regional talents. The performer’s list kept on growing in recent months: it seems a second Asian hub for *doromb* is in the making here! The first Asian hub for *guimbarda* being, what else, Siberia. In particular Yakutia, the republic which carries the *timir khomus* as its emblem, because the Yakuts (or Sakha’s) are the world’s most fanatic makers and players of *pangapoans*.

https://www.jawharpfestivaltw.com/

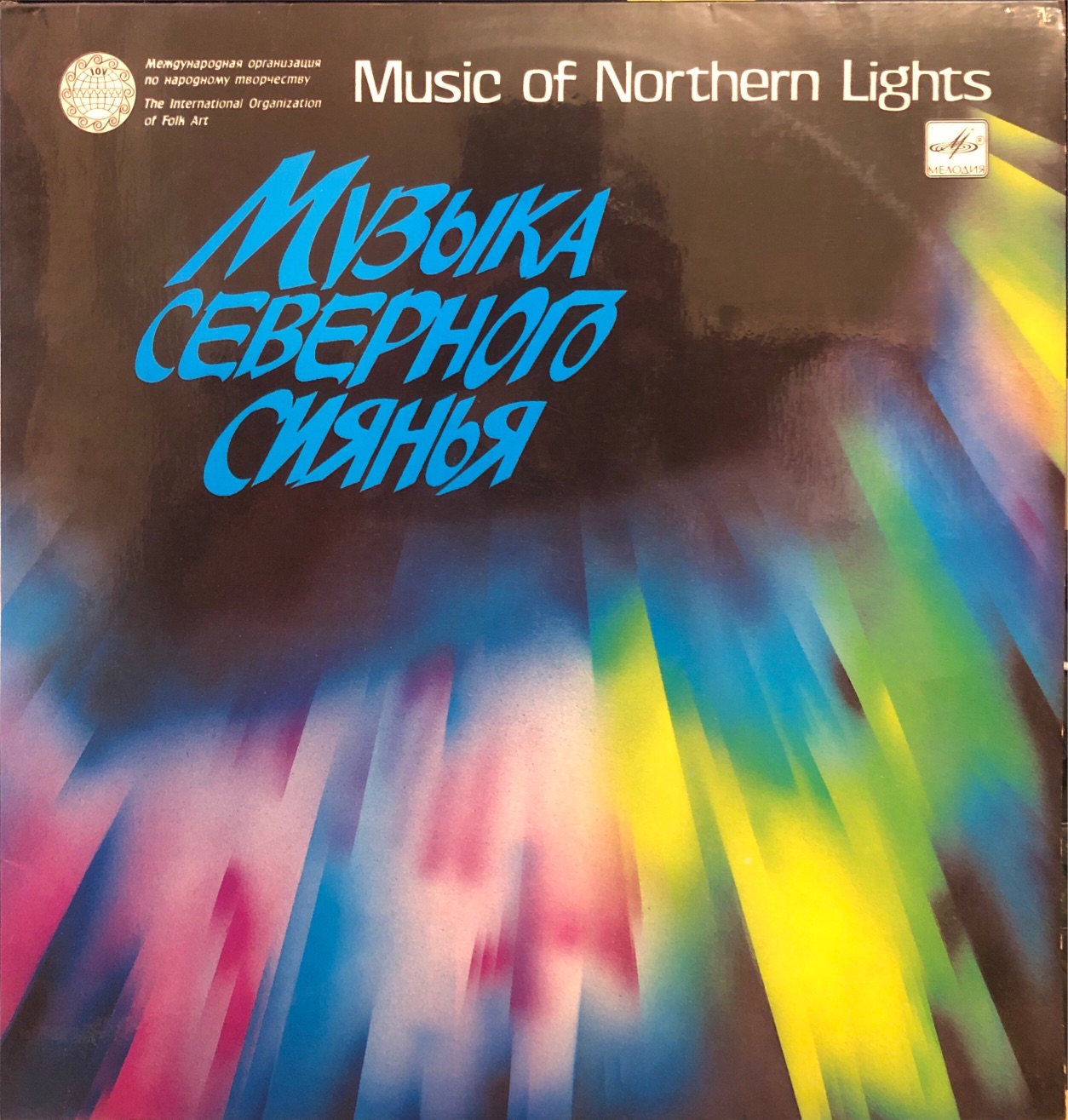

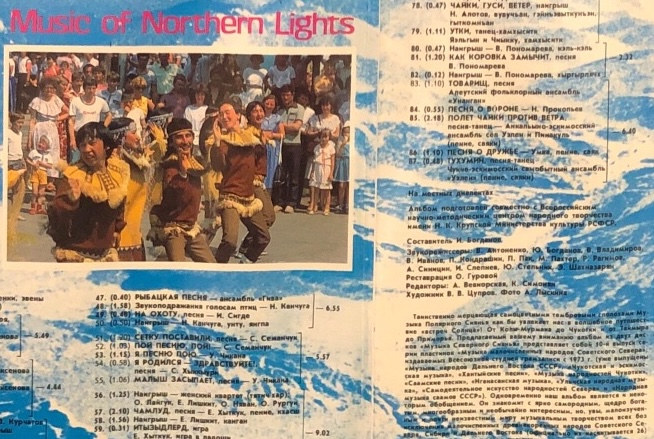

But who knows about other *gewgaws* in Siberia? What kind of *genggong* music do other indigenous people in Siberia have, such as the Negidaltsi, the Ket, the Chukchi – you probably never even heard the names of these people before (check out the map below to read all their names). So let me share some obscure recordings from the early days of my own *kunka* infatuation. I listened again and again to a double-album (2-LP) I bought in Moscow in 1992, an anthology of indigenous music from Siberia and Russia’s Far East. It was compiled by composer and music collector Igor Bogdanov (whom I met in Moscow in the year 2000, to learn more about an extraordinary triple album of Tuvan traditional music he had produced in the 1980s). There are a total of seven pieces with *vargan* players. This album, and my fieldwork in Tuva in 1993, is where I got my early *morchang* education: not from Yakutia, which is absent on this album (because it is dedicted to the “small-numbered” peoples of Siberia and the Far East). Besides the series of Siberian field recordings from Henri Lecomte on Buda Records (1992-now), each dedicated to one ethnic group, not much was ever published on disc for many of these peoples, as far as I know. And this two-elpee collection stands out as a fantastic introduction to the singing, the instruments and the shamanic séances of this gigantic landmass covered in permafrost. (There are quite a few other very obscure instruments, too).

We start with an upbeat style played on the *tumran* from the Khanti-Mansi people (the *names* I write here are the actual names in use by these Siberian peoples). The reverb you hear on all recordings was added in the studio: this was a standard procedure in folk music recordings for Melodiya Records. It adds a certain touch that over time became associated with traditional music recordings from the Soviet Union, and which, I have to admit, has its own charm.

Next is another upbeat piece from the Selkup, with two instruments indicated, each with a different name: *kypa* and *pyngyr*. Might these be two harps?

We continue with the lovely combination of the *pymyl*, together with the zooming disc mergeykoya from the Ket group. Listen to the lovely layered melodies from the *pymyl*, an octave apart: there is more going on than you might think.

Next are two pieces from Evenki, Eveni and Negidaltsy, the album notes do not tell which one is which.

The first one of these reminds one strongly of the Yakut style of playing and making *kumyzs*. The – presumably Evenki- instrument is called *kordavun* and is even tuned up a half tone towards the end.

The second of these one is the much lower, darker sounding *kunkakhi* of, I think, the Negidaltsi, with plenty of breathing sounds.

We move on to the Nivkh of the Far East, whose instrument is called *kangan* (pronounced as kan-gan) and with a very low pitch.

The last one is yet something very different, the very dynamic *vanny* from the Chuvash or Chukchi. My guess: the Chukchi, who are living next to the Bering straight. I have once seen a group performing in the Netherlands, with some fine *čangko’uz* playing.

Of course by now you wish to know: where to find these peoples? Here is a map printed in the nice 2-CD compilation The Spirits are Listening. Music of Indigenous Siberian Peoples by Henri Lecomte, whom I mentioned above.

Finally, let me be clear about President Isitolotolo: his election is not a joke, but it is not the end of the world either if you are in the other camp. The Dutch historian Johan Huizinga had this to say about American politics, in his groundbreaking 1938 study Homo Ludens:

More obvious than in British parliamentarianism is the Game element in American political mores. Long before the two-party system in the United States came closest to assuming the character of two teams, whose political difference was hardly distinguishable to the outsider, the electoral propaganda there completely took the form of great national games. The presidential election of 1840 created there the style for all later ones. Candidate then was the popular General Harrison. A program his supporters did not have, but a coincidence gave them a symbol, the log cabin, the rugged log cabin of the pioneer, and with that sign they won. Nomination of a candidate by largest volume of votes, i.e., by loudest shouts, was inaugurated by the election of 1860, which brought Lincoln to his post. The emotional character of American politics already lies in the origins of the national character, which never denied its origins in the primitive relations of a pioneer world. Blind party loyalty, secret organization, mass enthusiasm, combined with a childish desire for external symbols, give to the element of play in American politics something naive and spontaneous, that the younger mass movements in the Old World lack.

That was looking back into the 19th century, and up to Huizinga’s time, 1938. On the previous page Huizinga writes:

Modern culture is hardly ‘played’ anymore, and there where she seems to play, the play is foul. Meanwhile the distinction between play and non-play in the phenomena of civilisation becomes gradually harder to make, as one approaches one’s own time.

Nearly 90 years later things have changed, but reading the words of an original historian and cultural analyst can help us see that our current epoch is not the only one dealing with extreme situations.

My advice: use your *trump* / *lubuw* / *khomus* etc. wisely, as the Italians do: as a *scacciapensieri* – a *thought dispeller* or *gedachtenverdrijver*!!