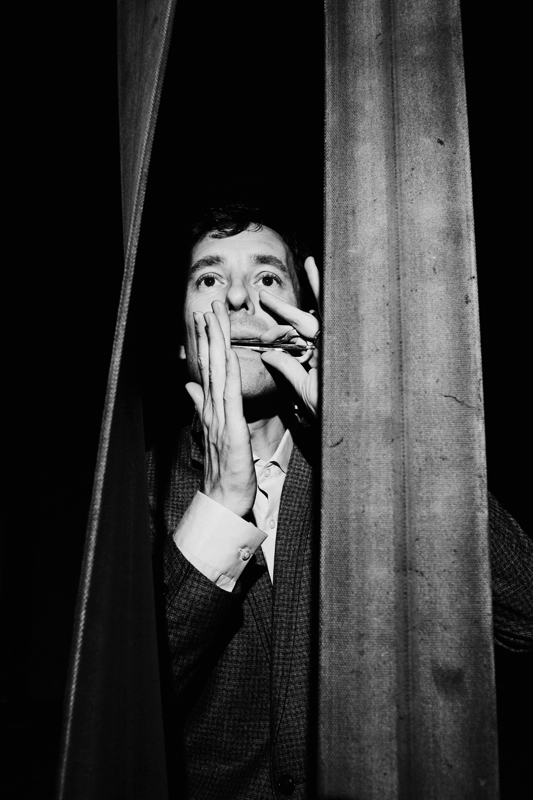

The most prolific researcher in the field of overtone singing is a man with many faces. His name is Tran Quang Hai and you can call him (and all options are correct): Vietnamese or French; a professional musician or a professional musicologist; an instrumentalist or a singer; an improviser or a composer; a traditional, a popular or an experimental musician (all three will do); an expert in Vietnamese traditional musics and an astute chronicler of its year-to-year development in the past decades.* Tran Quang Hai has a new book out celebrating his 50 years of music research in many different areas. We recently met in Paris, where he shared some interesting facts about the Vietnamese Jew’s harp (dan moi) I did not know before. On the trip back to Amsterdam I read most of the articles in his book that I had not seen before, so more on that too. Before talking about our meeting, his book and the origin of the word dan moi (Jew’s harp), some historical background. Since Hai is Tran Quang Hai’s first name I will refer to him as Hai.

I learned of Hai’s work on overtone singing in the early 1990s. When I got to know him personally, I was astounded and (I will admit) a bit intimidated by his unbridled energy. He loves to share what he does, and he is in fact overflowing with enthusiasm: for overtone singing, for Vietnamese music, for playing the Jew’s harp and spoons, for ethnomusicology, for his constant travels as a performer and teacher. After my visits I was usually exhilirated (about all the new things I had learned or shared with him) and at the same time exhausted (feeling my life was a mess with no progress at all).

In fact, going to Paris has been almost synonymous with visiting Hai and his lovely wife Bach Yen (whose singing carreer goes way way back). And these visits became almost synonymous with absolutely great Vietnamese food. Bach Yen often spent hours and hours to buy fine ingredients like all kinds of fresh leaves, vegetables, seafood and meat and prepare them the Vietnamese way. We would have excellent diners, drank nice wine, as the couple made an annual ‘pilgrimage’ to different regions in France to stock up on boxes of quality wine to share with friends at home.

After moving to Taiwan, my encounters with Tran Quang Hai were scarce, and visits to both of them even more. In 2019, it has been around ten years since we last met in Paris. So I was delighted to see them again some weeks ago. Tran Quang Hai retired a decade ago from the ethnomusicology department at the Musée de L’Homme in Paris, but has remained an active performer and workshop leader for all these years. Bach Yen is a famous singer of popular songs and entertainment music, as well as a singer of many different genres of traditional music. Together they have given hundreds of concerts in Europe and elsewhere, and they continue to do so. Here is a photo of their appearance in Genoa, Italy, a week or so after I met them.

Late August, when I walked down the platform of Gare de Lyon, Hai and Bach Yen were waiting for me. Once again I was overwhelmed to be in their buzzing, energetic presence. The first thing they did, was to get out their cameras and make many photos together. Then we strolled to their car, and their warm hands and arms embraced my arms. I sometimes think of myself as someone who easily touches people, but this time I thought I am quite distant compared to them. It was really (excusez le mot) touching to stroll down the platform chatting and to be ‘wrapped’ by their tender hands and arms on both sides. Hai told me once about using his hands to heal people and showed me some methods. But it seems the couple just radiates warmth and energy naturally, even without using a special method.

For our Vietnamese food, this time we drove to a place called Pho Bida, pronounced Fo Beeyaa. Pho is the famous Vietnamese noodle soup, but what about Bida? It turns out to be derived from ‘billiard’, as the former location of this restaurant housed a popular billiard room as well. The place is not very spacious but we were early and could chose any seat. By the time we left lots of people waited outside. The food was great and loved by Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese alike: highly recommended! (Pho Bida Vietnam, 36 rue Nationale, 75013 Paris)

Tran Quang Hai’s New Book

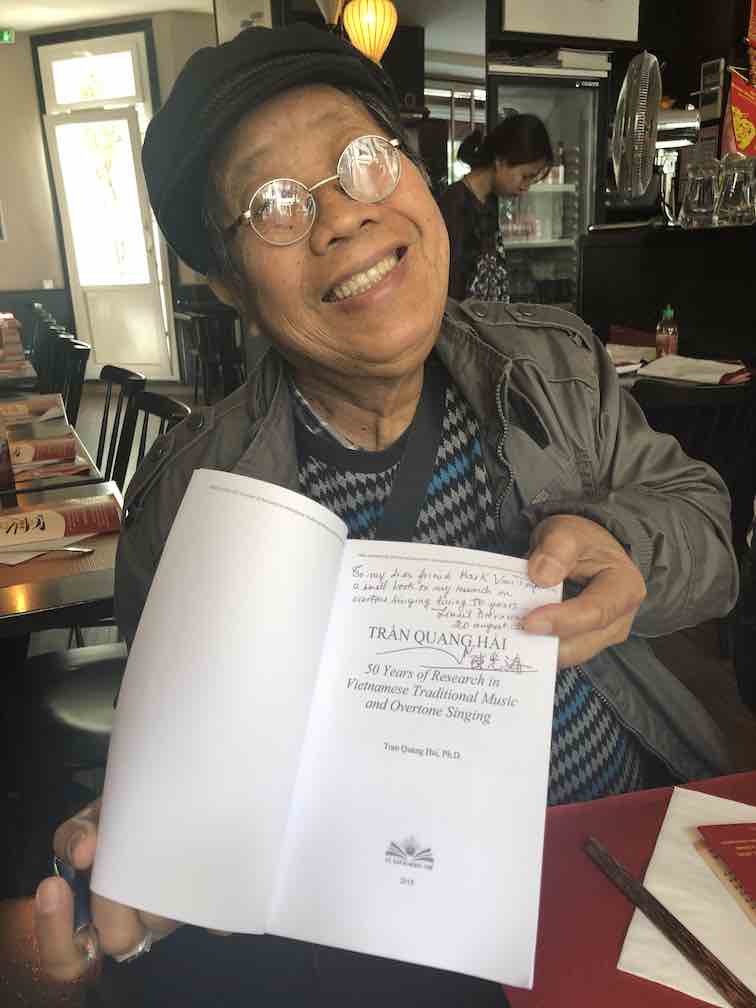

When we sat down, Hai gave me his new book, a thick volume with many of his articles and listst of all his achievements, titles, appearances, etc. organized in a single volume. Some articles I have known for a long time. So I particularly enjoyed reading those things I did not know in detail.

First, an article about Vietnamese music and its historical background, very helpful for understanding the relationship to Chinese music and culture. It also covers many of the recent developments in Vietnamese music, making it in effect a kind of encyclopaedic entry into Vietnam and all its music. With this work Hai most clearly follows in the footsteps of his late father Tran Van Khe, also a well-known musician and musicologist.

“Tran Quang Hai. 50 Years of Research in Vietnamese Traditional Music and Overtone Singing.”

Second, an article that accompanied a double CD issued in France in 1997, dedicated to the absolutely fascinating world of mountain tribe musics in Vietnam. There is a dazzling array of types of instruments and ways of playing, and these liner notes give a good overview of this field.

If you are interested in overtone singing and still love printed matter, as I do myself, then this is a good way to get your (physical) hands on several key articles on this technique by Dr. Tran Quang Hai and understand the background of his research. (Note for academic readers: for research purposes it is better to consult online pdfs of the articles in their original format). Available here.

Tran Quang Hai and the Dan Moi

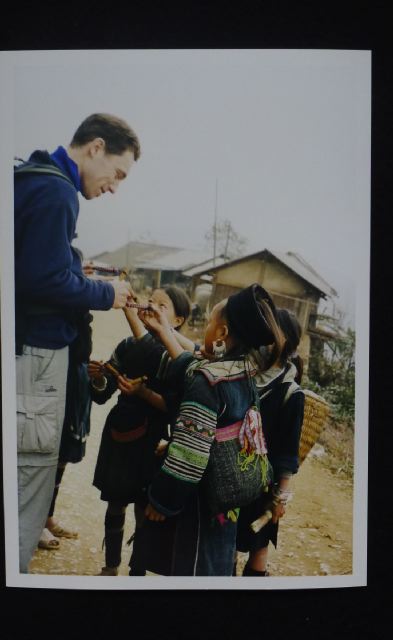

During our lunch I also learned where the common name of the Vietnamese brass Jew’s harp comes from. It is usually referred to as dan moi, which is a Vietnamese word (compare for example dan tranh/đàn tranh, the plucked zither, or the unique one-string zither dan bau/đàn bầu). However, the thin, finely crafted Jew’s harp, probably smaller than any other type of Jew’s harp, originates from the mountain tribes who live close to Yunnan in South China. The Hmong’s native language and culture has little to do with that of the dominant Viet or Kinh ethnic group, who are historically tied to China. When travelling in the mountains in North Vietnam (around Sapa), I encountered the Hmong people who play this instrument and managed to get one made locally by their craftsmen. They referred to it as gya, phonetically speaking, though in writing it is referred to as djam. A personal note from Tran Quang Hai shortly after publishing this post: the Hmong name of the Jew’s harp is ncas (pronounced ncha).

The djam I bought in Sapa from girls who played the instrument along the mountain road. (photo by the author).

So I asked Hai how the name dan moi came about. He explained: there is no Jew’s harp in the music of the ethnic Vietnamese. So when he learned about the traditions of the mountain people around 50 years ago, he had to make up a new name himself in order to accommodate the minorities’ instrument in the system and language of Vietnam. To use ‘dan’ (meaning ‘instrument’) was an obvious beginning point. Hai decided to add ‘moi’ for lips, to designate it is played between the lips. Most brass or metal Jew’s harps are held against the teeth, with the lamella vibrating between the teeth; the dan moi is held between the lips and vibrates there. In this sense it is more like a type of wooden or bamboo Jew’s harp, particularly the ones vibrated by a string attached to one side.

A Hmong girl playing the djam for me in 2003 (photo by the author).

The dan moi went on to become a very popular instrument around the world once non-Vietnamese musicians discovered them, at the turn of the millenium. Many people asked me for it when I brought them back in 2003. I remember giving one to Tuvan throat singer Sainkho around 2004. She immediately fell for its bright sound and expressive qualities, and asked for more several times after (and so did other people). At the same time, a German company saw the potential of this cheap instrument to reach a huge audience and set up (web)shop, calling it www.danmoi.com. It has a become a one-stop shop to buy all kinds of Jew’s harps. So dan moi, Hai’s new name for the djham, a minority instrument, and for Jew’s harps in general, now has become sort of a symbol of 21st century global Jew’s harp culture. And it seems to be growing year by year: here in Taiwan I have seen many new Jew’s harp enthusiasts taking the stages recently, often sporting a collection of world Jew’s harps, including, of course, the dan moi.

Here is a video where you see the movement of the dan moi lamella in slow motion, played by Hai’s student Dang Khai Nguyen.

Learn more about Tran Quang Hai

Hai is still actively teaching, find out where his next workshops are by going to his blog:

https://tranquanghaisworldthroatsinging.com

(the blog itself amounts to a ‘wikipedia’ of sorts for throat/overtone singing, where you will find a huge amount o copies of scientific and popular articles, videos, and indeed copies of wikipedia entries, as well as some original posts about Hai’s workshops and travels).

Go here to find more entries in English and in Vietnamese:

https://tranvankhe-tranquanghai.com

And for more news from Fusica and Mark van Tongeren subscribe to these blogposts here.

Finally, back to some Asian flavour, but East-Asian instead of the South-East Asian of Hai’s origins. Here is a hilarious video from the time Hai was flown into Japan to demonstrate overtone/throat singing in a hypertheatrical popular entertainment program.

TRAN QUANG HAI on JAPANESE TELEVISION, part 2, December 26, 2012

* OK, for this one I have no way to tell if it is true, but Hai does mention in his new book (page 32) that he wrote “more than 500 articles in Vietnamese for 30 Vietnamese magazines in America, Europe, Asia and Australia.”