Last Thursday I was in Tainan for a performance with other artists working in Taiwan and the Netherlands. It was organised by the Platform for Artists Netherlands Taiwan (PANT), which is mostly active in The Netherlands to help out visiting (or resident) Taiwanese artists. Or, in their own words, “a cross-cultural hub open for all the Taiwanese and local artists, culture workers, curators and everyone interested in Taiwanese cultures”. They held talks in the Netherlands, and now, for the first time, in Taiwan. Already interesting in itself, but the visit also brought some surprises. First something about what I knew was going to happen, the other artists.

Audio-visual-data artist Marije Baalman is having an exhibition at Soulangh Cultural Park and holding a residency there, with a workshop coming up in Taipei this week. She captured the sounds and the data of kites and wind in various ways, and turns it into a constantly changing sonic environment. You can watch and listen while lying on a reclining chair, with the sounds playing softly from padded loudspeakers besides your head. Marije’s new book about using data to produce sounds and other artworks was litterally rolling of the presses as we talked. One distinction I learned from talking to her is that there is not only sonification (using any kind of data to calculate a musical outcome, like different notes, timbres, durations) but also audification (the same happening in real time).

Live, performing after me, there was Yen-Ting Lo, a jazz vocalist-composer who studied and worked in The Netherlands for many years. She returned from Amsterdam to Taiwan last year and played some of her songs. She uses lots of ingenious modulations and was backed by a fine band, The Yen-Ting Lo Quartet (drs, bss, gtr + vcl/kbd). They premiered a piece where the audience can decide live which instruments are going to play, with an online tool. You could see the audience chosing drums and bass more often and then hear them fill in the next section, with guitar and keyboards stopping. Most of all, I liked Yen-Ting’s fluid melodies. One song reminded me of Trygve Seim’s Rumi Songs, with vocals by Tora Augestad. What a gorgeous voice!

The event was organised by Fu Wen-Chin who also had her own exhibition of instruments made of sugar. Very appropriate, in a former sugar factory, but that is a mere coincidence, as she has been making these hard sucrose discs for about 5 years now. And sounding they do! Most of the ones hanging there had a nice, hollow ‘ring’ to them. Others had sort of cracked and lost their ring, even though they were not broken. She mostly lets other performers play. Unfortunately I missed her playing for a camera crew, while I was having diner, but the video should be online sometime soon I guess.

On top: Yen-Ting Lo Quartet. Bottom: Marije Baalman, Fu Wen-Chin, Mark van Tongeren

The extra surprise of this visit had to do with my interest in the Dutch historical era in this area. I noted we were close to the territory where the Dutch interacted with the local Siraya people, almost 400 years ago. I was corrected: we were really in the heart of former Siraya territory. And next door in the same Soulangh Cultural Park was a permanent Siraya exhibition! I knew the Siraya were all-important at that time, but I was still curious to know more about the Siraya today… Well there it was, an exhibition showing how in the centuries after the Dutch left, the Siraya gradually became assimilated with the Han Chinese. They were marginalised as a distinct ethnic group and lost most of their unique culture, like other people classified here in Taiwan as ‘pingpu tribes’: the ethnic groups that lived on the plains, and not in the mountains. Those plains were flooded with ever more Chinese immigrants, as well as with rice paddies.

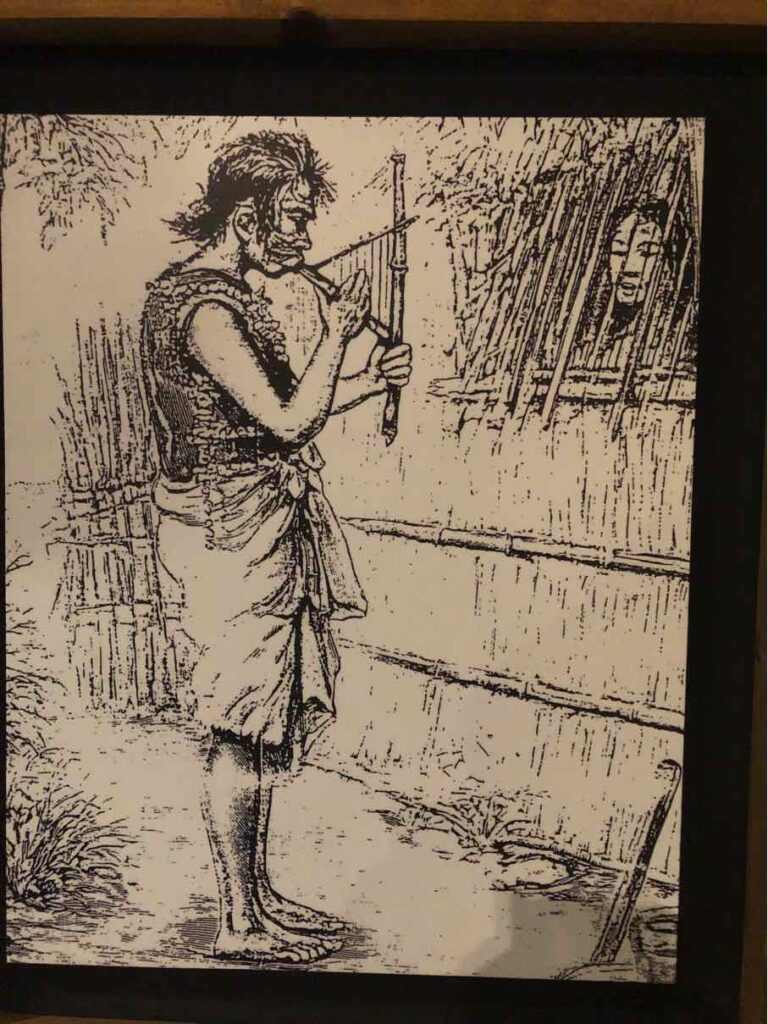

One drawing in the exhibition caught my attention: it pictured a Siraya man holding in his hands, and in his mouth, something that seems like a very unusual instrument. It has the shape of a harp, but a very tiny one with some extremely short strings. (I would say the shortest are about the length of the wire of an egg-slicer that you might have in your kitchen; I have occasionally used its high, thin twang to play or sample.) For a harp, it is rather short, and held a in strange fashion, in front of the player’s face. And then, it is also stuck in his mouth, as if it were a flute. But it looks like his lips are all around the bamboo tube, which is not how flutes are usually placed. So what is this? A mouth resonator for an unusual harp? It could be, if the bamboo is open at the mouth’ end. But with lips closed tight around the tube, the resonance, which can be modified with the tongue and jaw, would have to go out through the nose. And with such short strings, there is not too much to be expected from resonance. Maybe I got it all wrong and it is not an instrument?

Entrance to the exhibition; Photo of the Siraya, around 1900; Drawing of Siraya man playing a very unusual musical instrument

I do think it is though, and I put the question to the people of Soulangh Cultural Park, who would inquire with the curators. As I expressed my desire to search for its possible real-life form, and to find out how it could sound, I realised that I happened to be in very good company at this moment. I was in the presence of two ladies who are both members of the Instrument Inventors platform, or iii! What could be a better start to find out how an instrument like this could have sounded? With the “iii platform” just beginning a collaboration with the Soulangh Cultural Park, I hope that it will be possible to find an answer and that I can be part of bringing the sound of this instrument alive. Maybe together with a Siraya artist? Let’s see.

https://instrumentinventors.org/artists/

2 thoughts on “Dutch-Formosan Connections”

Comments are closed.